Evelyn Waugh, whose manuscripts and 3,500-volume library are now at the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin, was an inveterate collector of things Victorian (and well ahead of most of his contemporaries in this regard). Undoubtedly the single most curious object in the entire library is a large oblong folio decoupage book, often referred to as the « Victorian Blood Book. »

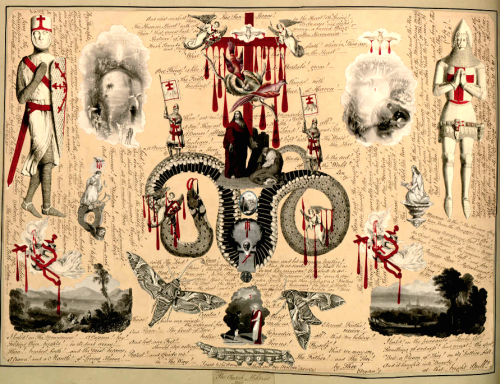

Its decoupage was assembled from several hundred engravings, many taken from books of etchings by William Blake, as well as other illustrations from early nineteenth-century books. The principal motifs are natural (birds, animals, and especially snakes) and Christian (images of the crucifixion, scenes from the Bible, and crusaders). Drops of red india ink and extensive religious commentary have been added to many of the images. The craftsmanship is exquisite, and after more than 150 years, the adhesion of the decoupages is still perfect. The book bears an inscription by one John Bingley Garland to his daughter Amy and dated September 1, 1854: « A legacy left in his lifetime for her future examination by her affectionate father. » Shortly afterwards, she married the Reverend Richard Pyper, so the album was probably an early wedding present. A 2008 Maggs Brothers catalog includes a group of eccentric decoupages taken from one or more albums, described as being in the style of the Pre-Raphaelite artist Edward Burne-Jones. The style and content of these works, which feature groups of angels and blue or gold doves, are aptly described as « weird » and « rather elegant but very scary. » They are unmistakably from the same hand as the Waugh book.

The existence of other such items suggests some kind of mass production, yet internal evidence indicates otherwise. John Bingley Garland was a prosperous Victorian businessman who moved to Newfoundland, went on to become speaker of its first Parliament, and returned to Stone Cottage in Dorset to end his days. A document still in the Garland family bears the same sanguinary ornamentation along with his signature. J. B. Garland’s will mentions in passing « all the mythological paintings in the Library purchased by me in Italy »—perhaps a small clue to his artistic interests? Most importantly, the inscriptions in the dedication and the text are in the same hand. In recent years scholarship has focused on the significance of Victorian scrapbooking, which was almost exclusively the province of women. Scrapbooking was largely a means of organizing newspaper clippings and other information; the esthetic aspect was entirely secondary. In the lack of any information to the contrary, this apparently conventional paterfamilias must be regarded as the principal, if not the only, begetter of the decoupage, and if it was his alone, he must have spent hundreds of hours at the task.

How does one « read » such an enigmatic object?

We understandably find elements of the grotesque and surreal. But our eyes view it differently from Victorian ones. As Garland’s descendants have written, « our family doesn’t refer to…’the Blood Book;’ we refer to it as « Amy’s Gift » and in no way see it as anything other than a precious reminder of the love of family and Our Lord. »

The first plate contains a short table of contents and the title « Durenstein! » (Dürenstein, the Austrian castle in which Richard the Lionhearted was held captive). The title and the theme of many of the plates relates to the spiritual battles encountered by Christians along the path of life and the « blood » to Christian sacrifice. According to the Garland family, « it is full of symbols of both Human and Non-Human ‘Crusaders and Protectors’ of God and Christianity and most of the Verses, Quotes, etc are encouraging one to turn to God as our Saviour. »

Vous devez être connecté pour poster un commentaire.